Sounding Glass

Length: 10:00 mins

Year of production: 2011

Exhibition Format: Quicktime file

Source Format: 16mm archival footage and Super8

Language: No language

Selected Music by: Thomas Carnacki

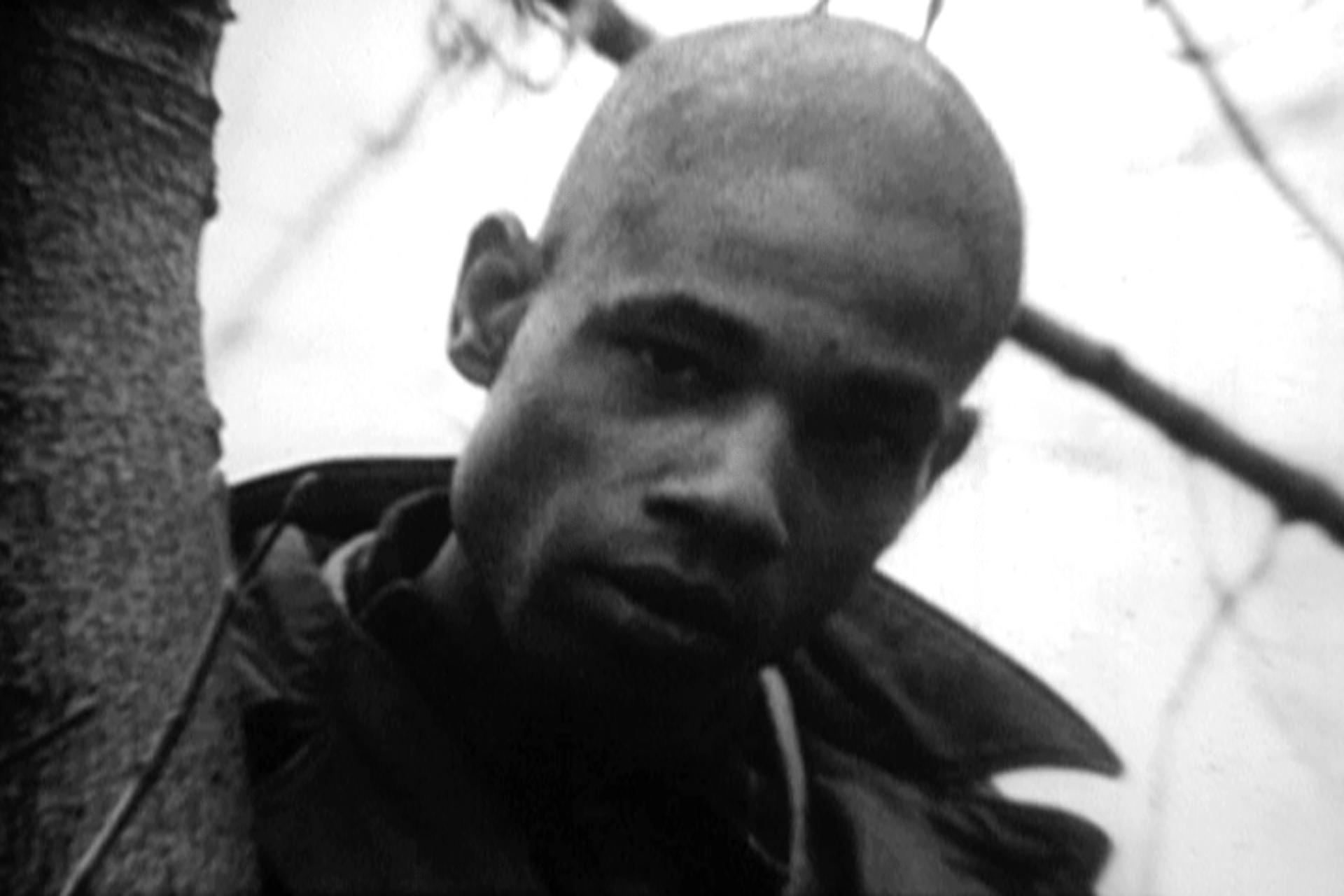

Synopsis: A man in a forest is subject to a flood of impressions; rhythmic waves of images and sounds give form to his introspection.

Short Statement: I was interested in creating transnational and transhistorical connections by juxtaposing protagonists, that, on first sight, don’t seem to belong together, but may very well have had close personal, familial, cultural, and historical ties.

Long Statement: Sounding Glass alludes to the known but mostly under-represented history of mixed-race children that came out of American and Japanese unions immediately after World War II, in occupied Japan. Many of these children were orphaned when their American fathers left the country and their Japanese mothers couldn’t face societal pressures on their own. Half-Japanese children with African-American fathers were often considered particularly hard to assimilate. Many stories of these mixed-race children have been largely obscured or forgotten, leaving them not just familially orphaned, but historically orphaned as well.

In my experimental short, I wanted to retrieve parts this history; and while my approach is entirely fictitious and speculative, my aim was to create affective transhistorical relations. The concept was to make an entire film made out of the smallest fragments: cutaways, supplementary and even accidental shots, gathered largely from 16mm orphan film: newsreels, educational, and amateur films that have been abandoned by their owners. The fragments work on multiple levels: in a structural and rhythmic capacity, and as a mnemonic device. But they also work as a metaphor, for the splintered nature of human memory; and at the same time, for history in a broader sense, which often consists of dominant narratives that focus only on selective elements of the past, excluding and erasing the experiences of more minor narratives.

I picture the man in the forest to be one of the grown up half-Japanese orphans, the forest symbolizes an internal, introspective space. Some of the 'mnemonic images' in the film show snippets of quotidian scenes that seem insignificant; but for me, it is often precisely these random images that are charged with an affective familiarity comprising a sense of home: a father leisurely rowing a boat, a woman embracing her lover, a drive into a home town, a grandmother doing laundry, fishermen hauling their catch of the day. The quotidian images are interwoven with images from the specific transnational historical conflict, WWII, that fundamentally marks the man's heritage.

In the second half of the film, there are close up images of a female eye; this is the only material not sourced from found footage––I shot this Super-8 footage of my Japanese mother’s eye. On one hand, this footage is a compositional element that provides visual cohesion, but on the other hand, I indirectly insert myself, if removed. This particular footage symbolizes the act of seeing and relating, and connecting to a story much larger than our own.

In the ending sequence, there is a row of people waiting in line, as if to find out some result, outcome or judgement that would impact, even determine their future trajectory. The footage is superimposed with a pan across barren trees in the forest. The faces of the people are obscured, they are turned away from the camera and have an almost ghostly appearance. To me, these people become symbolic for the specters of unspoken or unarticulated narratives.

I edited the two image sequences, frame by frame, in a way that has them alternating, flicker and superimpose simultaneously, which not only took away the sharpness of the standard flicker effect, resulting in a more gentle throbbing quality; and most notably what I call the ‘rolling’ effect—as if the images appear to be rolling, like waves, across the surface of the screen. This editing pattern becomes the point of departure for a series of subsequent films, Sea of Vapors, Wishing Well and Labor of Love, in which I further explore, develop, and deepen the visual language of said ‘rolling’ effect, adding more complexity with each film, more layers, color, and a vortex effect to the basic structural approach that I first discovered in Sounding Glass. (Berlin, March 8, 2021. Sylvia Schedelbauer)

Poem by Katue Kitasono,

from Black Fire, 1951.

Translated by John Solt

MONOTONOUS SOLID

in the mirror

turtle's

egg

burst

summer's burst

gloom's

shadow's burst

that bubble

that hopeless

wing

or

that

avalanche

of

clouds

one drop

of my location

and

stripe

of tragedy

and

circle

of loneliness's

head

verticality

that

blanc d'argent

that

illusion

that

burst

imagination's

face's

curved line's

dark

jaw's

hard loneliness

that craving

voice

is full of

gloom's forest

the day

also passes

for

an extremely fast

fly

needle

of white cone's

distance

needle of bread and

water

lead moon

repudiates

lead flag

dream's

butterfly's

burst

on

top of smashed plates

still voluptuously

fragrant

black firearm

death's

burst

inside

hot glass bottle

star's

water's

dahlia's

extraordinarily visible burst

–––This kind of history lies at the edge of vision – it is seen through another’s eyes, observed and gathered around a separate body, felt in waves and pulses through a sense deferred. Winter leaves, the forest floor. (Ben Russell, program notes, Berlin Documentary Forum 2)

–––In a forest a man watches us, contemplating our gaze through the apparatus. A dramatic story is written on his face and amplified by the emotions that suffuse the work. While the camera slowly zooms into a close-up on his face we see flashes of images: burning buildings, people with their backs turned, trees again. The title references sounding boards and looking glasses – the aural and visual components of cinema, also the polemical and the analytical. We may take this as the artist’s most profound statement on both the medium and the subjects that concern it. (Greg de Cuir Jr, program notes, Academic Film Center Belgrade)

–––Sylvia Schedelbauer’s films are composed predominantly of pre-existing footage, material that she draws from educational, industrial and amateur collections that includes home movies, travelogues and newsreels. The un-captioned segments, although extensive, are characterized by what art historian Charles Merewether describes as the ‘countermonumental’ – no landmarks, iconic events or familiar historical figures appear. In Sounding Glass ...we see snapshots of a forest, a murmuration, explosions on a battlefield, a Japanese woman carrying a baby on her back, sun bursting through the clouds. In their original contexts, these shots were cut-aways, fillers, accidents even, expressions of what is typically overlooked but presented together here, they amass as a portrait of a splintered collective psyche. Sounding Glass features a protagonist though, a man who stares intently into the lens of the camera at the film’s outset and about whom all the film’s questions of cultural dislocation caused by global conflict relate. (Alice Butler, exhibition booklet, Grazer Kunstverein)

–––With very few images culled from the flood of footage originally taken during World War II, the filmmaker manages to express the incomprehensible trauma of war as a strong visual experience. With a highly compressed use of sound and image, Sounding Glass creates a visceral impact that can only be achieved by cinematic means. (Jury statement by Steve Anker, Birgit Hein, Karina Karaeva, Masayuki Kawai. International Competition, International Short Film Festival Oberhausen)–––The certainty that everything and everyone has a fixed place in history gives way to uncertainty and searching. Constant changes between light and dark set history in motion. Flickering deforms, developing a pull that in turn creates an urgency that doesn’t preclude doubt. (Jury statement by Jan Distelmeyer, Andreas Siekmann. German Competition, International Short Film Festival Oberhausen)

–––The power of sound becomes visually transmitted in Sylvia Schedelbauer’s imposing Sounding Glass. The film meditates on the lasting resonances of violence imparted first through a strobe effect, flashing between a shot of trees and blackness. This device has the power to imbue a still image with immense movement, impart an ominous threat onto neutral foliage, and create a mounting sense of tension... (Aily Nash, Brooklyn Rail)

–––[Schedelbauer's] unique mode of montage, which follows the basic rules of found-footage jump cut collage but softens the edits with rapid fades, produces a highly unique viewing experience, one that approximates the drift and slippery-sand pacing of oneiric images across the mind's "mystic writing pad."... (Michael Sicinski, Academic Hack)

–––Sounding Glass […] begins with a black-and-white image of a tree behind which a young man emerges, gazing steadfastly into the camera. The filmmaker takes this image as an opportunity to reflect on the history of those children who emerged from Japanese-American connections in Japan after World War II. The narrative Schedelbauer distills from found footage, which consists of everyday scenes as well as images of wartime action from World War II, is speculative. But she is more concerned with "affective transhistorical relations," as she herself puts it, than with the reconstruction of historical facts. The image of the tree is a possible mnemonic image and at the same time, as in Wishing Well, the trigger of a flood of audiovisual impressions, which here are clearly connected to a traumatic experience. (Claudia Slanar, catalogue text, Blickle Kino, Belvedere Vienna)

–––Sounding Glass (2011) is another journey into these liminal, mnemonic spaces, in which Schedelbauer’s use of found footage, and particularly here of 16mm ‘orphan film’ (an umbrella term that emerged during the 1990s among archivists to describe moving-image work abandoned by its owner or copyright holder for lack of commercial potential; the concept was later expanded to refer to films that had suffered neglect), is mirrored in the film’s own significance. A man, described by Schedelbauer as ‘one of the grown-up half-Japanese orphans’, stands in a forest and stares into the lens of the camera, acknowledging and sustaining our gaze, before disjointed images of quotidian life are juxtaposed. The flicker is employed extensively in the work with a hypnagogic effect, while the forest surrounding the man seems to allude not only to a place of personal introspection but also to a spiritual locus, a mycorrhizal network of splintered human interconnections reminiscent of Tsing’s organic assemblages. (Ren Scateni, Art Review) –––The phenomenon of perceptive persistence theorized by Gestalt psychology (psychology of form) is that phenomenon by which our brain creates the movement of an image even where it does not exist, thanks to a succession of still images, projected one after the other in the fraction of a second. This possibility, this latency of the image in our brain gives us the possibility to see reality in different ways and from different emotional points of view. The structure of this video is based on the phenomenon of image persistence having been realized like flashes with, at times intimate movement, sometimes interspersing the flow of images that are already in motion. The result is an alienating vision of an inner world. The man in the forest looks at us and we look inside him, through him, in his nightmares, in the images that perceptively remain on the retina. (Stefano Romano, program notes, Art House Shkodër)–––Der Experimentalfilm von Sylvia Schedelbauer, die an der Universität der Künste Berlin bei Katharina Sieverding studierte, gehört zum Genre des ‚Found Footage’-Films. Es ist seit 2004 das fünfte Werk der Künstlerin, das dem Prinzip einer assoziativen Montage folgt, bei der die verwendeten Bildfragmente den Zuschauer auf einen neuen Erfahrungshorizont einstimmen. Ort, Zeit und inhaltliche Bezüge werden bewusst offen gehalten. Kaskaden von disparaten Eindrücken – das Gesicht eines Mannes, Naturskizzen (vor allem Waldbilder), Kriegsszenen, Fischerboote, Frauen im Kimono, Menschen in einer Reihe, mit dem Rücken zur Kamera – fesseln die Aufmerksamkeit. Das Ganze ist kein Bildkontinuum, sondern eine stroboskopisch schwarz-weiß flackernde Licht- und Schattenfolge. Die Anstrengung beim Wahrnehmen dieser Bilder ist gewollt: die extreme Verfremdung ist ein selbstreflexiver Hinweis auf ihre Konstruiertheit. Der darüber gleitende elektronische Sound von Thomas Carnacki gibt dem Flackern zumindest akustische Stabilität. Das erzeugt eine erstaunliche Sogwirkung, obwohl bald die kognitive Schmerzgrenze erreicht ist. Es bleibt aber zu spüren, dass sich die in Gang gesetzte Assoziationskette nie in Beliebigkeit verliert, sondern genau das Maß von Bedrohlichkeit erzeugt, das mit dieser virtuos-sperrigen Gestaltung gewollt schien. (Jury-Begründung, Prädikat wertvoll, Deutsche Film- und Medienbewertung)

Awards:

2012 Gus Van Sant Award for Best Experimental Film, Ann Arbor Film Festival

2012 Special Mention. International Competition, International Short Film Festival Oberhausen

2012 Special Mention. German Competition, International Short Film Festival Oberhausen