Sylvia Schedelbauer Interview

Recycling orphan films to (de)construct identity

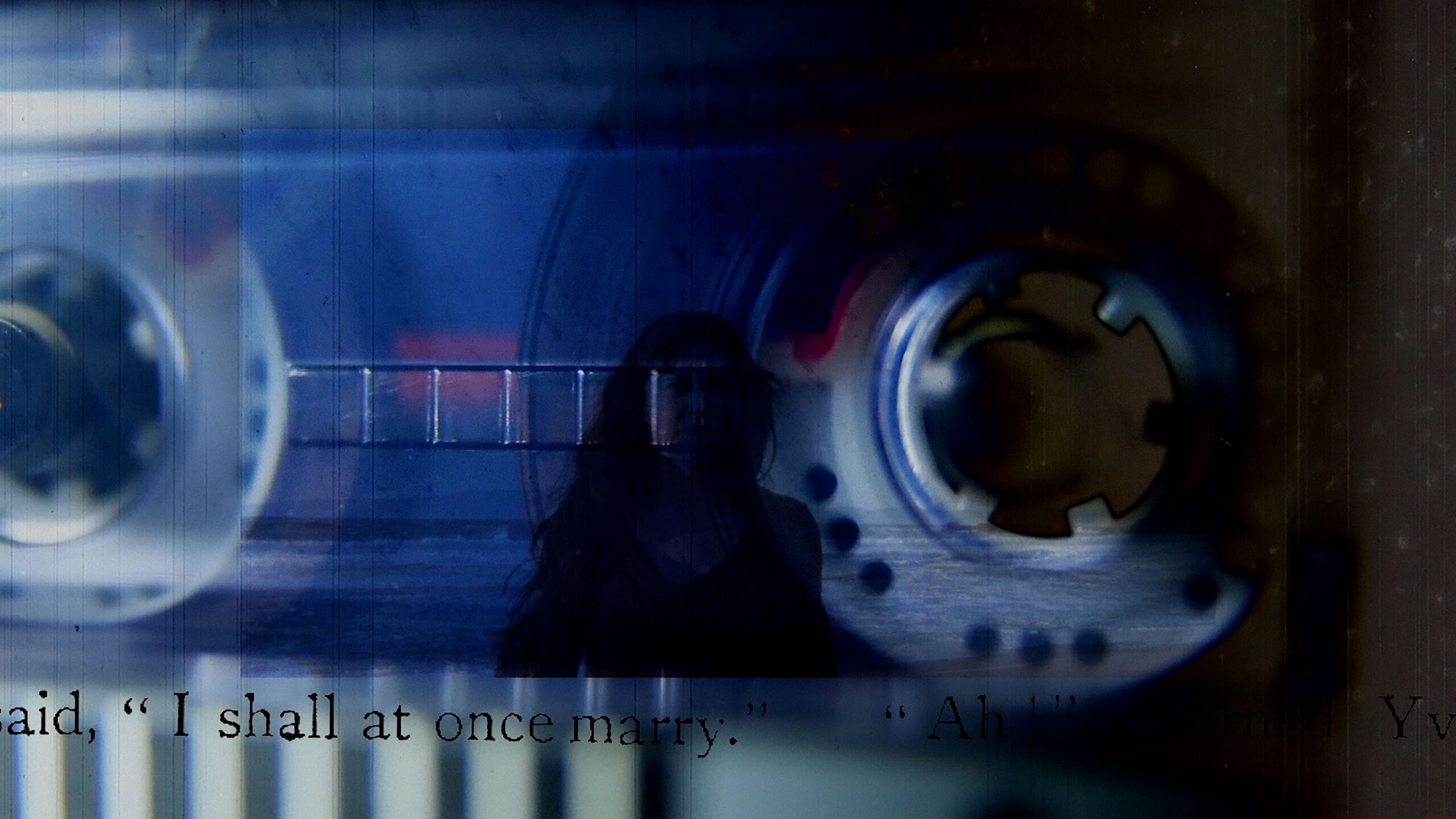

A conversation with german-japanese artist Sylvia Schedelbauer on transnationality, originality, and the construction of personal and collective identity. By Ivčo Ružić, for kulturpunkt.hr

The recently held 25FPS festival featured a retrospective of work by artist and filmmaker Sylvia Schedelbauer, whose films negotiate the space between broader historical narratives and personal, psychological realms, mainly through poetic manipulations of found and archival footage. The themes she works on revolve around history, memory and transnational identity, and in this conversation we worked out the details of the ideas she developed with her co-panelists at the round table Challenges of Film Preservation and the Aesthetics of Recycled Film.

As you work a lot with film archives and orphan films, I was wondering how accessible you find archives, both in terms of viewing the footage and material and in terms of using them to be reedited and implemented within a new work?

It's hard to speak about this in general or global terms, because every country or location will have their own situation. But it’s definitely harder to gain access to materials from archives in Germany, say, than in the United States. I’m not saying it’s impossible, but it’s harder because none of the following legal terms exist: Orphan films, public domain, and fair use. So even if, for example, the Bundesarchiv (national archive) in Germany held an amateur film that has never had a copyright, whose author and provenance was unknown – a classic orphan film, really – the archive would still not release it for creative use, because someone at some point may possibly show up and say: “that’s a film that family member XYZ shot,” thus claiming ownership. Of course, if you have a very specific project, you can seek to receive support, and it may be granted, but you would likely need a very big budget. You have to be very specific about what you're doing, and that would require knowing exactly what you are looking for and why.

My work is a lot more process based, that means I usually have no idea what the film is going to be like at the beginning of the process, but that also means that I can’t always say what footage I am looking for. For my filmmaking, open access is important because I need to be able to freely browse material, and to get to know films and their footage, in order to find out what’s possible on one hand, and to get inspired on the other. In Germany, for example, access is extremely regimented: one puts in a request for a film, then the archivist comes and threads the film, and then you can see the film in what feels like a very distant process, you look at the images without ever touching the materiality of the film itself. In the US, both at the Library of Congress and at the National Archives, as a researcher, one is granted direct access to the films, that is to say, you receive a short orientation, put on special gloves, and then you yourself handle the films: you thread them on the flatbed and are left alone with them. You have the freedom to take as long as you want, rewatch the films as many times as necessary, as long as you remain within, obviously, the opening hours. You can work through the films in your own time, without having to worry about taking too long. Liberally browsing archival films is something I truly love, and is really necessary for the way I work with material.

As to working archival film material into artworks: looking at films and using them for your own work are two completely different questions. If using material from an institutional archive, one must usually clear the copyright question. Most of the films in the National Archives in Washington DC are copyright-free, whereas most films held in the Library of Congress were at one point copyrighted, so that question must be cleared first. Once the copyright question is cleared, one can obtain digital copies that one can work with for a transfer fee…which isn’t exactly cheap. As to the German context, the process is so complicated and closed that I haven’t even gone there to try to work with the archives.

How does this closed-off-ness of certain archives influence your work flow? Do you focus more on traditional, factual investigation like who, what, when, or a more emotional form of research, trying to grasp the feel and emotion the films contain and show?

Yes, of course it influences my work, in that I simply don’t go to the archives that won’t allow a more open access. It’s hard enough as an experimental filmmaker who doesn’t make money from their work, so I’m not going to add more hardship by torturing myself with closed archives. It’s crucial to be able to see, spend time with films, and intuit, which is harder if an institution is very closed. I don’t usually approach an archive with a documentary, or as you say ‘traditional’ approach of finding one specific event or person, although I have kind of done that in one of my most recent films on the opera ‘Madame Butterfly.’

For the most part, my work is a lot more process based, and requires browsing an archive to get a feeling for what I can or cannot do. I try and see what images say to me, and try to use them in a poetic and metaphorical way.

I’m also a keyword searcher, I like to see what I can find on specific keywords regarding nature, like trees, landscapes, or on the ocean… browsing material that doesn’t immediately seem to relate to the questions I am working on allows me to have surprises and be inspired to work in a direction I didn’t anticipate at the beginning of a process.

In my experience, archives are often tied to particular nation states - was it difficult to work with themes and narratives of cross/transnationality? Are there references to migration and the movement of people within archives?

Yes, of course national archives are always tied to nation states, and in consequence, what archives hold closely mirrors official historical narratives of a country, that is to say the material is usually made by and made for members of a dominant cultural and social group. So material that relates to minorities is often handled from a centralized gaze, that of the dominant culture. I can’t generally answer your question about references to migration and movements of people, as one would have to look at very specific examples in their specific contexts. I am sure that you will find films made by white Germans on the histories, for example, of the migration of Turkish workers and their families to Germany as part of the historical labor campaign. How these films represent people who have migrated and if they speak to the experience from within is a different question. Of course there are many other narratives of migration to Germany, and whether all minorities are represented and how is yet another completely different question. As for my own experience and the history I focus on, it’s very complicated because the history of mixed, transnational, European-Japanese subjectivities is scattered across different archives in very different locations, so it’s very much a work of patching together different fragments from different sources.

I was also wondering, what does get archived? Have you noticed other specific dominant narratives that have to be rewritten or are multiple voices represented?

It’s hard for me to say in general terms what gets archived and what doesn’t. I’m neither a historian nor an archivist, nor an academic who works on film history—I’m merely an experimental film artist who works with pre-existing motion (and still) pictures. However, it’s a really important question that should be put forward to any institution and archive. While I can’t answer that question from a scientific point of reference, I can give an impression gleaned from experience. National archives generally seem to hold material that was once made by a governmental institution, either for educational, informational, or, in some cases, for military, state intelligence, or even propaganda purposes. What gets archived is that which has been declassified, or which has been deemed historical. But again, that depends on the archive. Then, in addition to that, what usually also gets archived is all that which has been copyrighted and deemed relevant by a cultural or educational institution. The contents of an archive will focus on historical events that have dominantly shaped the narrative of a country, so minor narratives are often harder to access. But this, too, depends on many other factors, such as how big the minority is and what perceived impact it has had on the fabric of a dominant culture. What an archive holds can also be contingent on the purpose of the archive, so, for example, the Jewish archive in Germany will obviously hold material that pertains to the history of Jewish subjectivities in Germany, (and, for example, there is no designated Palestinian archive here). The Asian American and Pacific Islander Collection (at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.) holds material that highlight Asian American and Pacific Islander cultures in the United States. The more marginal a minority is, the harder it will be to find it represented. Having said all this, it obviously also depends on the location of an archive and to what capacity it can devote means to maintaining its collections. What if the archive is located in a war-torn country? How complete can an archive be if records have been burned or destroyed? What happens if there is an archive but no money to put into the work of restoring films and saving them for posterity? What happens if this restoration work can only be done with outside, international funding? What factors come into play as to which films are deemed important and less important? It’s all quite complex, I don’t think there are easy answers to your question.

Along those lines, and in relation to your film Erinnerungen, did you notice any diverging ways of constructing national and personal identity around war, maybe as either negation or confirmation/reconciliation of the past?

I was born in Japan to a Japanese mother and German father and I’ve always been interested in questions of history, perhaps because historical events shaped the trajectories of both my parents. When I was growing up, history was always referred to through a monocultural lens, in my case, either through the German or Japanese lens. I think that always made me feel slightly out of place…because I never felt that I completely belonged. Much later, after I made my first work, I started being really interested in finding out more about the entanglements, interconnectedness, or complexities of histories. I've also made more abstract ‘painterly’ work, but those are some of the questions I always return to.

But if you take national narratives and how a country comes to terms with history and the past, again, that depends on location. I’m not sure there can ever be one answer to how countries deal with questions of responsibility, reparations, or coming to terms with past actions, especially if they involve war crimes. If you look at the German and Japanese contexts, they both have similarities in their histories of colonial aggression, dispossession, and devastating war terror and crimes. But coming to terms with these historical facts is very different. The narratives are constructed completely differently, and the way these narratives were written were also influenced by outside factors, such as the occupying presences of American, British, French, and Russian forces in post-War Germany, and the American political influence in post-War Japan, and the mounting cold war. How the war crimes were processed seemed to be contingent on the political interests of outside forces. How history is reproduced and made accessible (or obscured, even erased) through educational institutions is a whole other story, and that also depends on context.

On a more personal level, in a way, how I made my film Memories somewhat mirrored how history was accessible to me. There was a lot of weight on the national-socialist past on the German side, the effects the war had had on my father’s family and how he could not find work in Berlin, how that lead to the labor migration of my father to Japan. There were many images that came from his side of family, and so the focus naturally fell more on my father’s side of the story. There were very few images of my mother’s past, certainly none from her childhood or youth. There was also very little information about her past, so there was very little I could work with.

I feel like one of the techniques you use in your films is also abstraction, and I was wondering if you think that offers more space for these multiple, nonlinear narratives? As history is subjected to distortion regardless, do you think abstraction mitigates that by allowing countless more distortions, allowing for more interpretations, that are varied and form a far more complex image in the end?

I do think that abstract films offer more space for interpretation. I never expect any audience to read my films in any one way. But I would be cautious to say that I deliberately create distortions in the sense that I alter historical facts. The perceived constraints of spoken language were the initial reason to move towards abstraction. When I made my first films “Memories,” I had a box full of photographs from my father’s side of the family, images of his mother, his father and my grandfather, but I had very few images from my mother. The weight of the images influenced the way I constructed my version of the family history. It was a university assignment, meant as an answer to the question ‘How do you see yourself in relation to war?’ So that film was my answer, and an excuse to finally use the photos I had discovered a long time ago as a teenager. I wrote the voiceover text in one go, like a stream of consciousness, I never really edited it. But the text in the film makes me cringe to this day, as I have come to realize my own biases and mistakes. It’s funny, Lucija Zore, who was on the Found Footage panel at 25FPS, and who attended the retrospective screening of my work, was the first person ever to point out to me that I had miscalculated my father’s age at the end of the war. That’s not the only mistake I made in the film, I also miscalculated my own age in the section where I visit Roppongi as a teenager. I didn’t intentionally make these mistakes, nor was I aware that I was making them when I wrote the text for the film. I took note of them quite soon, but I decided to keep it all in there as this reflects what I was thinking or believed at the time, and to somewhat be fair towards the subject matter and to how I treat my parents in the film.

But I became acutely aware of the limitations of spoken language, and how prone to mistakes and gaps any narration of events can be. I wanted to explore these themes from a more non-verbal approach, that is to try and use images and sounds and montage to create films that perhaps touch upon these questions, but leave enough openness for audiences to make their own meaning and interpretation of the films.

You’ve also spoken about simultaneity in the past - how do you think our experiences and conceptions of time and space have evolved? Does this influence how you go about using historical as opposed to more contemporary found footage, if you even view them differently?

Ross Lipman made a comment on my work during the Found Footage panel that in my film “Oh, Butterfly!,” there wasn’t just one, but multiple things happening at the same time, and that there were many different entryways to the film. He related that to the kind of internet behavior where you bounce from one thing to something else. Maybe that did inform me, but I’m not so sure. Using the internet and multiple platforms for communication, including social media, may have altered the way I think or feel about time and space. But the first time I thought about simultaneities came when editing my first flicker films, “Sounding Glass” and “Sea of Vapors.” I began intercutting contrasting elements such as darkness and light, here and there, then and now, fast and slow, etc., and I always related these simultaneities to feelings of wanting to be in more places than one: for example, wanting to be in Europe and Asia at the same time, as that kind of longing was very powerful in my childhood and youth.

I noticed you address the films, words, and works you reuse as quoted, borrowed, or diverted - is that how you view your process, as a conversation with previous ideas and expressions? Do you see political implications in this freer form of sharing and collaborating on the construction of ideas and expressions?

I think there are different modes of thinking and approaching art making . I understand why people insist on authorship and if somebody wrote a brilliant book or somebody made a fantastic painting or film and if they say they are authors of original work and they would never want to do this kind of recycling in art or in film, that’s their prerogative and I respect that. But I think I have drifted towards this other mode of thinking where you think about yourself as the sum total of outside influences—that may also be due to my mixed heritage.

All my life people have interrogated me about my heritage, people have asked: “Are you really half-Japanese? Do you really speak Japanese? Are you really who you are?” On the other hand, people have ironically also claimed to know about me better than myself, they have “race-splained” things to me. When a person or a group of people make a self-declaration about who they are, then they should be respected for that and not be asked questions like “is that really true? How can that possibly be?!”

In my experience as a mixed-race or intercultural or transnational person you’re supposed to have answers for everything, and if you don’t know one small thing, people happily jump to conclusions: “There! How can you not know that? You’re not really who you say you are!” Somehow it is expected that you have to be better than 100%, you have to be twice as good as a mono-cultural person, you have to speak the language twice as good and know answers to everything for people to finally accept that you are who you say you are.

Which obviously is preposterous and you should be able to relate to a culture because you have a personal or familial relationship to it and you should be able to claim that heritage. Perhaps because of this background I have a slight allergic relationship to notions of originality, perhaps that’s the reason why I am happy to work with pre-existing footage, creating unexpected connections, relations, and kinships through them.

I'm more interested in a culture of sharing and collectively thinking about image production. Ideas around fair use and public domain, etc. have much informed my practice. I don’t like the notion of originality - I would much rather think from the perspectives of linguistics like Roland Barthes said - everything we say is informed by influences and quotes that we read or heard before, and I think that's a much healthier way of thinking around art practices as well. As Jim Jarmush has said, something to the degree of “steal as much as you like- as long as you make your own thing out of it.” Or Jean-Luc Godard said: “It’s not where you take things from - it’s where you take them to.”

Do you approach using commercial and public footage in a different way as opposed to private footage, be it material stemming from your family or a stranger?

I’ve used photos and super 8 material from my family archive, and I used a lot of newsreels, educational films – most of the material is in the public domain, i.e. those films don't have any commercial value, nobody cares about them anymore and the copyright was not renewed so that's all orphaned material. I have also worked with Hollywood B movies, amateur films, and stock footage – so there is different types of source material. I can’t generalize how I approach the material because it always evolves in the process. But during the editing, everything is treated in the same way, whether the footage comes from my family or is found elsewhere, everything is cut up, composited, superimposed, and blended together.

In my most recent film, “Oh, Butterfly!”, I tried to find as much material as I could about the opera Madame Butterfly. I tried to track down every film that was ever made, there actually aren’t that many, but in the past 100 years, every decade or so there has been a new film. And I tried to track down the most famous recordings of the opera and then of course there are the books that the opera is based on, and there is the famous aria. I worked that all into my film, even if in minimal portions. And of course, most of that material is copyrighted. As I said in the panel, I use the material under the fair use clause: I quote the material and use it together with other quotes to form a larger argument, in my case closely looking at the history of the myth that the opera is based on.

Many people around the world know the melody of the famous aria – “Un Bel di, Vedremo,” but do they know what it is and what it says? As recent as the Tokyo Olympics, Nike produced an ad in Italy, featuring the aria in the soundtrack. What does that all mean, and what does it say, subliminally? I feel like with music it's so interesting because it does something with your subconscious, and I was interested in how music, too, can create biases. Anyway, that was a slightly different mode of working than when I know that a material is from public domain and copyright-free. My editing approach depends on the source material. But I often think about footage in the form of quotes that I am borrowing to express an argument, or in this case, in order to make an allegorical, self-referential film about the opera.

I feel like your films intertwine these influences, both personal emblems as well as bigger picture notions very eloquently, dealing both with personal and collective memory.

It's always an entanglement – at the festival there was a film by a Croatian filmmaker - Valerija, by Sara Jurinčić. In the film, the filmmaker goes on a journey to visit her deceased grandmother’s grave, and Jurinčić beautifully fragments photographs of her female ancestors, uses multiple projections, composites of different images, and also projects the graveyard portraits onto her own face. It is at once an intimate encounter with the filmmaker’s ancestors, as it is about acknowledging that the women who came before her are a part of who she is today. We all carry parts of our families within us, in that way, Jurinčić‘s film is universally relatable.

So when working on films, I, too, try and see how to create complexities, and see how I can work in various influences—personal, but also coming from larger society or history.

Finally, I was wondering how you view your use of landscape and nature in film? For me, it felt like you referenced landscape as an often collective experience and highlighted the political potential of nature and the environment as something that feels, rage for instance, together with us.

I moved to Germany when I was about 20 years old - and one of the first things I noticed is how the light was different. It took me forever, possibly even decades, to get used to the fact that there is less sunlight in Germany and that the light looks more yellowish. For many years, even now, I still miss the pacific light - it’s very bright, very white in the summer, and it makes everything look different - the way you look at nature, landscapes, or even a city. When I moved to Berlin I felt I also really missed mountains and the ocean and various landscapes from Japan. Berlin has its own charm, its plain and flat landscape, and so I realized that nature and landscapes are another aspect of how you relate to time and especially a place. It's not just culture, it's not just identity, it's not just the people, the food and the way you live, but it's also the larger landscape that surrounds you, how you feel at home in it, how you feel connected to it and how you take pleasure from nature. And it took me a long time to appreciate the German colors, I mean they are also beautiful, just entirely different. That was another aspect in trying to deal with these questions of being in a place and identity, identifying.